Faculty Chairs Leading the Charge

Guiding Teaching and Research at the Highest Level

By Sarah Brenner Jones

At Rice, excellence is not an either-or proposition. While some universities prioritize teaching and others focus on advancing research, Rice aspires to lead in both. This dual objective is at the heart of Rice's 10-year strategic plan, which aims to elevate Rice as the premier university for teaching and research.

Fueling this ambition is an extraordinary faculty that specializes in the power of “and” — scholars who are advancing the frontiers of knowledge and preparing students to meet the challenges of tomorrow. Their ability to innovate as scholars and inspire as teachers is what sets Rice apart.

Endowed chairs are critical to attracting and retaining these visionary scholars. They provide the resources, recognition and freedom to pursue ambitious research, mentor future leaders and elevate entire fields of study. Because they are permanent, they represent a legacy of excellence — a single chair can influence generations of students, research and public discourse.

The impact of endowed chairs is best illustrated through the work of three remarkable Rice professors. In biosciences, a trailblazer is unlocking how life works at the cellular level, while mentoring the next generation of leaders in synthetic biology. In economics, a leading researcher unpacks the forces behind inequality and opportunity in the global economy. And in the humanities, a Shakespeare and environmental studies scholar explores the role of bees in Elizabethan England, offering fresh insights into how we perceive nature and society today.

Each of these faculty members brings extraordinary vision and dedication to their work, and each is empowered by the support of a named chair. Their stories reveal how philanthropy fuels excellence today and for generations to come.

Scroll Down To Read More or Jump to the Stories Below

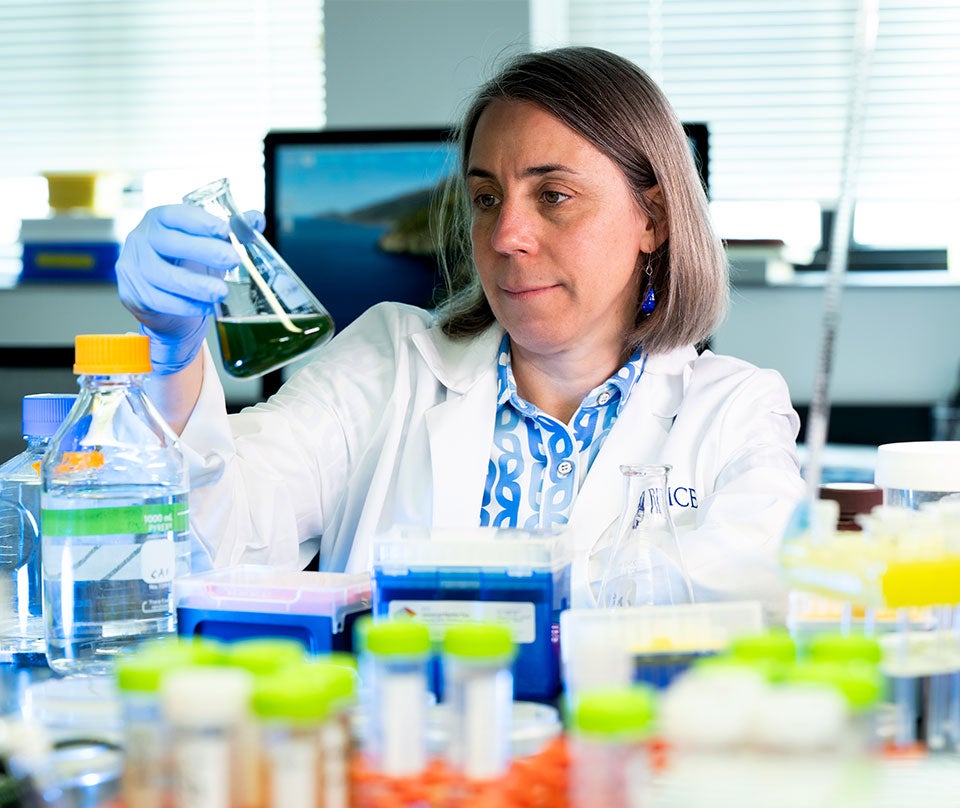

From Molecules to Materials

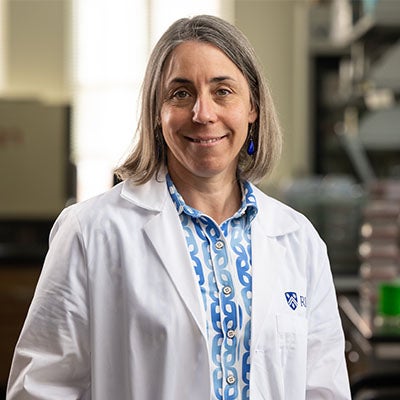

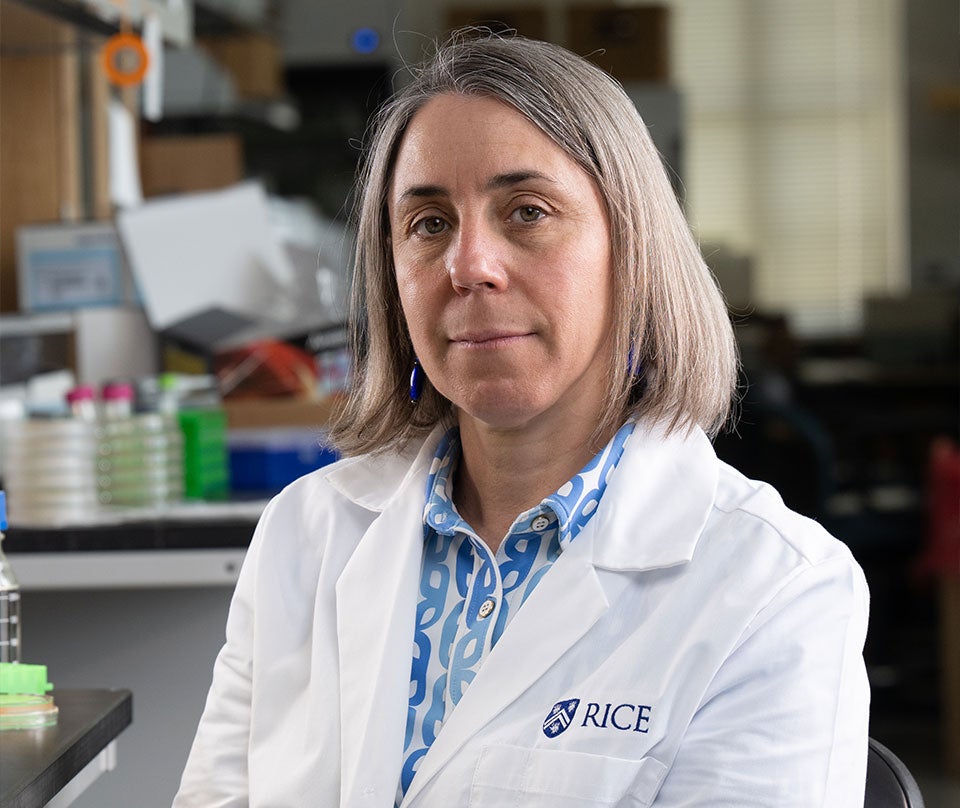

Caroline Ajo-Franklin and the Future of Engineered Biology

In Caroline Ajo-Franklin’s lab, biology isn’t just studied — it’s imagined, engineered and brought to life in surprising new forms. A single cell becomes a stretchable rope. Microbes are programmed to sense toxins and respond with precision. At this intersection of nature and technology, Caroline is reimagining what biology can do and is mentoring the next generation of scientists to do the same.

Recently, Caroline was named the Ralph and Dorothy Looney Professor of BioSciences. For Caroline, the chair is more than an accolade. “Being awarded the Looney Professorship is a great honor,” she said. “I appreciate the respect of my colleagues and the administration, and a chair shows that you have that. It also gives you freedom.”

Freedom, Caroline explained, is what lets science move at the speed of curiosity. “Sometimes you have an idea for a collaborative project and just need a little data before writing a grant. Or you meet a student or postdoc whose skills are exactly what your lab needs. Discretionary funding from a chair lets you take those small but crucial steps. It’s a little investment that can yield much greater scholarship and research.”

Though all of her degrees are in chemistry, Caroline has always been driven by scientific curiosity across disciplines. Her Ph.D. focused on biophysical chemistry, blending biology, physics and traditional chemistry. But it was the early days of synthetic biology that caught her imagination, when researchers began programming cells to do things like store memory or carry out computations.

“What drew me in was the richness,” she said. “Nature does extraordinary things — just look at a tree. Trees turn carbon dioxide, water and sunlight into wood, a material that’s stronger and more flexible than much of what humans can manufacture. My lab asks, ‘How can we use biology to build better materials, and how can we do it sustainably?’”

Caroline’s team designs living organisms that function in surprising ways. In one example, they engineered a single bacterial cell to grow — over the course of just two days — into a centimeter-scale rope with remarkable stretch. Cut a piece of that rope, leave it out for weeks, then place it back in a culture and it will grow again. It’s like a biological 3D printer. “We’re interested in how these materials could be useful in low-resource settings,” Caroline said, “whether that’s space travel, disaster zones or parts of the world without infrastructure. If you need a strong, elastic material, you can grow it from a seed.”

Her work also bridges the natural and the fabricated. The lab explores how to make biology “speak” the language of electronics. Cells might sense environmental hazards and trigger useful responses, like releasing a polymer to trap pollutants or making enzymes that neutralize toxic compounds. “We’re trying to understand how biology can sense, respond and communicate,” she said. “That opens up all kinds of possibilities, especially as we think about the needs of a growing population and a planet with finite resources.”

Caroline's team engineered a single bacterial cell to grow — over the course of just two days — into a centimeter-scale rope with remarkable stretch.

Mentorship is central to Caroline’s work. She leads a lab of 14 students — three undergraduates and 11 Ph.D. students — along with five postdocs, and sees guiding their growth as one of her greatest responsibilities. “One-third of my time is spent meeting with people in my lab, making sure they have space to talk — not just about science, but their careers, classes and lives,” she said. “It’s a joy to collaborate, and it keeps me grounded.” For Caroline, training future scientists isn’t just about technical skills, it’s about cultivating curiosity, resilience and the ability to solve complex problems. When students are empowered to follow their questions in the lab, they’re better prepared to think creatively and critically long after they graduate.

She also works to raise funds, advocating for and championing the work of her team. “Running a lab of this size is like running a small business,” she said. “I’m the HR department, the communications director, the one who makes sure the world sees the amazing work my students and postdocs are doing.”

“Biology is incredibly powerful,” Caroline added. “As researchers, we’re constantly toggling between discovery and invention. Endowed chairs help make that possible. They support risk-taking, collaboration and the mentoring that ensures science keeps moving forward.”

The Economics of Words

Flavio Cunha Makes the Case for Early Childhood Investment

In the quiet hum of a university office filled with papers and data sets, Flavio Cunha is leading a revolution — not with fiscal policy or stock market models, but with bedtime stories and family dinners. The Ervin K. Zingler Chair of Economics at Rice, Flavio is redefining how we think about economic opportunity: Long before a child enters a classroom, their potential is being shaped — not by wealth, but by words.

A pivotal moment in his intellectual and academic journey came during his doctoral studies at the University of Chicago when he encountered the landmark 1990s study by Betty Hart and Todd Risley, which revealed the so-called “30 million word gap.” By age three, children from higher-income families had heard roughly 30 million more words than their lower-income peers — a disparity with lifelong implications. Economic policy, he began to understand, is not simply a tool to manage markets, but can be a lens to understand and improve the conditions that shape human potential from the very beginning.

“I was so interested, because conversation isn’t income dependent,” Flavio recalled. “Conversations don’t cost parents money. A lot of the gaps we see arise from environmental issues that we don’t have to pay for. I wanted to know how we could use economic policy to improve those environments.”

That curiosity sparked a mission to implement real-world programs that empower parents and support children. “I don’t just want to write papers,” he explained. “I really want to change policy.”

To do this, Flavio knew he needed to teach parents what researchers already knew about child development and brain science. This led him to co-design programs that deliver this knowledge directly to families. He works closely with community organizations and school districts to design, implement and evaluate parenting interventions that can scale without requiring enormous resources.

One such program, the Jumpstart Program (JSP), was launched in partnership with Alief Independent School District in the Houston area. A seven-month initiative, JSP provides group and center-based training for parents of 3-year-olds to promote at-home learning and prepare children for pre-kindergarten. Families meet regularly at their local elementary school with the district’s family liaison, and children participate independently in monthly sessions.

Unlike many parenting programs staffed by highly trained researchers, JSP is implemented entirely by school district personnel using standard resources, making it both accessible and sustainable. “Our research asks a crucial question,” Flavio explained. “Can scalable programs implemented in real-world settings improve the home environment and enhance the school readiness of economically disadvantaged children?”

“I don’t just want to write papers. I really want to change policy.”

— Flavio Cunha

The answer, so far, is promising. A three-year randomized controlled trial of JSP found improvements in curriculum-based assessments and measurable gains in cognitive readiness. Perhaps most importantly, parents in the program reported reading more frequently to their children, with data showing that 75% of the program’s impact came from direct effects and 25% from changes in parenting habits.

Flavio’s goal is to move his research beyond academic journals and policy briefs. His work is a powerful reminder that economics, at its best, is a human science — it’s about people. As his research continues to influence policy and practice, the potential for broader impact is just beginning to unfold. The future he envisions is one where economic policy empowers parents, supports children and transforms opportunity from the ground up.

Where Bees, Books and the Bard Collide

The Scholarly World of Joseph Campana

For Joseph Campana, poetry, scholarship and teaching are tightly woven together — a triad inspired by the extraordinary educators who once showed him that literature is both art and a way of seeing the world. “My practice as a poet, my practice as a scholar and my love of teaching really goes back to having had extraordinary teachers for whom literature was deeply important,” he explained.

This commitment to teaching has guided his nearly two decades at Rice, where he is now the William Shakespeare Professor of English, director of the Center for Environmental Studies and co-director of the environmental studies minor. In each of these roles, Joseph fosters an intellectual community where literature, research and multidisciplinary thinking intersect. He is also co-principal investigator of Diluvial Houston, a Mellon Foundation-funded initiative examining climate, culture and community.

As both a scholar and an educator, Joseph is shaping a broader academic conversation. When he began teaching Introduction to Environmental Studies, he led a course of about 70 students from 25–30 different programs — 70% from STEM fields, alongside students in architecture, social sciences, humanities and even music. “What is fascinating and inspiring, as a writer, researcher and teacher, is grappling with subjects that are beyond all of us,” he said. “The scope is massive. The complexity is massive. And there is no single discipline that will have all the answers.”

It is precisely because environmental issues are immense and multifaceted that he sees environmental studies not just as an academic pursuit, but as a crucible for cultivating what he calls critical imaginations for the future. “Teaching about environmentalism,” he said, “is about various kinds of knowledge about how we live now and the realities of our world today. But it’s also about equipping students to ask informed questions and to imagine alternative futures.”

Joseph’s scholarship on early modern literature also focuses on environmental questions. His current monograph is a study of bees in Shakespeare’s England, a fascination that began in graduate school and has evolved into a rich scholarly inquiry. “People in early modern England were writing natural histories about insects, while at the same time, they were theorizing society,” Joseph said. “Bees became a metaphor for order — industrious, disciplined, collaborative. Virgil saw them as models for self-sufficient societies.”

“History gives us a sense that the world was different once and that it could be different again.”

— Joseph Campana

Joseph’s methodology is rooted in close reading, but his questions reach far beyond the historical page. “My tactics as a scholar are about looking very closely at works in their historical moment and then asking interesting questions that have an urgency in our own.” Whether he’s writing poetry, teaching Shakespeare’s plays or exploring how those plays have been adapted over time, Joseph sees literature as a record of human possibility. “I love the opportunity to have a little window into another moment,” he reflected. “History gives us a sense that the world was different once and that it could be different again. But it also reminds us how deeply connected we still are to those pasts.”

Joseph’s work resonates in the classroom, in academia and in the art world. At a time when environmental crises demand new ways of thinking, his scholarship and teaching model how the humanities can contribute to urgent global conversations. By drawing connections between Elizabethan bees and today’s ecological or societal challenges, or by guiding students to imagine alternative futures, he demonstrates that literature is not a retreat from the world but a tool for engaging with it.

Accelerate the Vision

Endowed chairs ensure that the brightest minds have the freedom to teach, mentor and innovate at the highest level. If you are interested in supporting exceptional scholars through endowed chairs, please contact Ginny Jones, executive director of development, at gbjones@rice.edu or 713-348-2096.

Explore More From Our Current Issue

A family creates a lasting tribute for a beloved sister and daughter.

Cordell Haymon ’65 and Walter Loewenstern ’58 share what inspired 45 consecutive years of giving.

The long-anticipated space will be a new hub for student connection, engagement and growth.